By Penny Niven for the 1967 edition of The Wisackyola Historical Festival Review, Waxhaw, NC

We used to vie for the first glimpse of the water tank and the smoke stack. You could see the water tank first, of course, if you were coming down Providence Road from Charlotte, and the smoke stack was more readily seen from the Monroe side of town. As the miles shrank, we watched and shouted, often before we really saw either, that the water tank and the smoke stack had come into view. Staunch vessels of two of the basic element of ancient days, they were symbols of Waxhaw.

The overhead bridge became a more important symbol of the town.

The bridge tied the hot dusty summer days of the present to the dustier, hotter summer days of the past, just as surely as it connected North and South Main Streets. The bridge was where boys loitered and where children peered with a nervous thrill at trains roaring below the cracks. It was where you ate your ice cream from Henry’s cool, dark drug store. It was where you fled on Halloween night when sand bags whizzed and water balloons popped and dripped in the October chill, and the Big Boys were escorted the Niven-Price outhouse on its annual Halloween excursion.

From the bridge you could see all over town on that long, liberating trudge home from school. When they narrowed the bridge, it seems as if the world were narrowed and constricting in its process of change. Perhaps the universe that seems so vast in childhood was simply coming into proper focus.

The churches, too, emerge in retrospect as proper symbols of the town.

It was on the steps of the Presbyterian Church that we discussed the future and love and life in the infinite leisure and optimism that only twelve-year-old minds can fathom. We trooped faithfully each New Year’s Eve, like wayward pilgrims, to endeavor to jolt the slumbering town with the strains of whatever raucous melody we admired at the moment, amplified to infinity by the Methodist Church chimes. We never quite lived up to the success of the legendary older generations, and always had to settle for just ringing the bell.

It used to be, in lucky summers, that you could go to three Bible Schools, with lemonade and cookies every day. On lucky Christmases you could hear three different Christmas concerts – or, perhaps, one huge, holly hung concert by the three church choirs combined, with splendid decorations, some shepherd in some father’s navy blue bathrobe, “Joy to the World” for a glorious finale, and hot Russian tea afterward in the church basement. Carolers used to wend their frozen way about town serenading shadow people in warm windows, with hot chocolate later to expedite the thaw.

We enjoyed a perpetual ecumenical movement, though we didn’t use that term, with the ministers Russell, Bangle, Martin, Joyner, Potter, and Perrell sharing the concerns of the whole town.

And there was the Saturday the Methodist Church burned, and the Sunday afterward when things went right on in the basement of the church, with wet hymnals and a wheezing organ and a bleak, smoke-scented January chill in the room. The rebuilding that followed was a symbol in itself.

Sidewalks were symbols, too, connecting like a fragmentary spider web the enterprises of the town. We hop-scotched and raced, and etched the names of a parade of sweethearts of chunks of Waxhaw pavement. Sidewalks led to school with its incredibly capable staff. For such a small town there was a chance in a thousand that each vital member of the minuscule faculty would know as much and communicate as well as these did. My colleagues and I knew something modern students often didn’t – that teachers are people. That made a difference, somehow when you had to be punished for some scholarly misdemeanor. The reprimand was much more personal, taking into account all ancestors, all family roots, all tradition. There was always a relative somewhere whose name needed to be lived up to or lived down.

The sidewalks led to the picture show, where we feasted our weeping eyes on Scarlett O’Hara in “Gone with the Wind.” We wept for days after “I’d Climb the Highest Mountain.” We didn’t discriminate much on Saturday afternoons. Randolph Scott or the Canadian Mounties or anyone on horseback would do, and a quarter got you in, equipped with faintly musty popcorn.

We sat on the sidewalks on moist summer evenings to count the lightning bugs we had stuffed into old mayonnaise jars.

We gathered in fascinated circles on the sidewalk to watch Duffy and Robert turn their eyes completely backward in the sockets. Sidewalks led to Mrs. Walker’s for music lessons, to Genny’s for brownies and Cokes; to Uncle Ben’s store for a Nehi grape or some cheese. Uncle Ben could cut exactly the weight of cheese you asked for without any measure but practice and instinct.

We formed many somber funeral processions on hot summer sidewalks and marched to lay to rest some poor deceased cat. (Loffie preached; I played “To a Wild Rode”; Patsy sang “Danny Boy:” everybody else mourned but Lynn, who was the pallbearer.) We lined the sidewalks the day Mr. Jessie’s bank was robbed. We didn’t know then that he would never quite get over it.

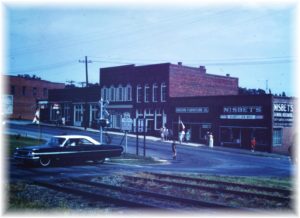

If you walked the Waxhaw sidewalks from one end of town to another (or if you ran away on them as certain children were wont to do), you passed the hotel, and the Niven-Price Company, with Mr. Sam Massey, keeping a smiling vigil. Steele’s shoe shop used to stand where the Post Office is, and Mrs. Texie’s variety store, Mrs. Romedy’s sewing shop, and Wade’s Barber Shop in a row next to Dr. Daly’s office. Mr. Jake Rodman kept shop on the corner. The Farmer’s Store, Nisbet’s, A.W. Heath and Hudson’s have survived, but on South Main, you used to find Mrs. Mary Belle’s shop and the movie theater, and the depot.

Nothing much ever really happened in Waxhaw, I suppose if you use today’s frenzied standards for measurement.

Babies were born, and people, sick and well, went about their business, and everyone else’s too, at times. Those babies grew up playing on the muddy, merry-go-round in the school yard; watching a Saturday afternoon ball game; going to a fish fry or camp meeting or a genuine Broadway theatrical production in the school auditorium; going to school and church and graduating and marrying and working and dying. Waxhaw changed slowly in ways you could see.

I can remember first seeing television in Waxhaw. I can remember when they put in a dial system to supplant the good old switchboard and its faithful, knowledgeable operators. What dial system could every tell you, when you called and got no answer, where your party had gone and when he would be back? I remember when they tore the depot down as if even the trains were too busy to stop and catch a breath. You might term my generation post-television and telephone, but pre-consolidation, pre-rescue squad, pre-Wisackyola, a town well (reconstructed) and town Christmas tree. These changes are welcome.

Still, when we come back for holidays, I am the first one to see the smoke stack. My nearsighted eyes first detect the tiny silver glint of the water tank. And I look toward the overhead bridge to be sure that boys still loiter and trains still pass there, and the bridge itself, like the identity of the town is still intact.

Penny Niven, a native of Waxhaw, graduated from Waxhaw High School in 1957. In 1961 she was a magna cum laude graduate of Greensboro College. In 1962, she received the Master of Arts degree in English from Wake Forest College through the courtesy of a graduate fellowship. Since 1962, Penny has been a teacher of high school English. This year she is engaged full time in research and writing materials for English composition and for teaching disadvantaged students. We are grateful for her story, Symbols of a Small Town, prepared especially for the 1967 edition of The Wisackyola Historical Festival Review.

(Photos were added to the article for this blog post and are courtesy of Kris B. Morefield.)

About Penelope “Penny” Niven (1939-2014) (from http://www.penelopeniven.org/about/)

Penelope Niven is the critically acclaimed author of Carl Sandburg: A Biography, Steichen: A Biography, and, most recently, Thornton Wilder: A Life. She and James Earl Jones co-authored Voices and Silences, praised as a classic on acting, and she has written a memoir, Swimming Lessons. Carl Sandburg: Adventures of a Poet, her biography for children, was awarded an International Reading Association Prize “for exceptionally distinguished literature for children,” one of six books honored among publications from 99 countries.

Penelope Niven has been awarded two honorary doctorates, three fellowships from the National Endowment for the Humanities, and the Thornton Wilder Visiting Fellowship at the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Yale University, among other honors. She received the North Carolina Award in Literature, the highest honor the state bestows on an author. During the past twenty-three years she has lectured across the United States and in Switzerland, Canada and Wales; has served as an editor for various publications; and has been a consultant for television films on Sandburg, Jones, and Steichen. She recently retired after twelve years as Writer- in-Residence at Salem College in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, where an international writing prize was named in her honor, along with the creative writing portfolio prize given each year to a Salem student.

Penelope Niven is the mother of award-winning author Jennifer Niven (The Ice Master; Ada BlackJack: A True Story of Survival in the Arctic; Velva Jean Learns to Drive; Velva Jean Learns to Fly; Becoming Clementine and The Aqua-Net Diaries.).

For more information about Penelope Niven, go to http://www.penelopeniven.org.

To hear more old Waxhaw stories join us

on October 14, at 7 p.m.

Joyce Blythe and Melvin Faris will host a night of storytelling.

Melvin is a Waxhaw native and Joyce moved to Waxhaw with her family when she just was six years old in the 1940s. Joyce and Melvin lead the historic Waxhaw walks in the the Spring and Fall each year.

Hear stories they don’t have time to tell on the historic walks along with other stories of the old days of Waxhaw. Other old Waxhaw folks will be joining them as well to tell their tales.

Mark your calendar! Limited seating is available.

Tickets: $15 and will be available to purchase online in September.

For those of you that have lived in Waxhaw a long time, don’t worry. The names will be changed as needed to protect the guilty.